Now Reading: Precious Moloi-Motsepe, Stitching Medicine, Purpose and Possibility

-

01

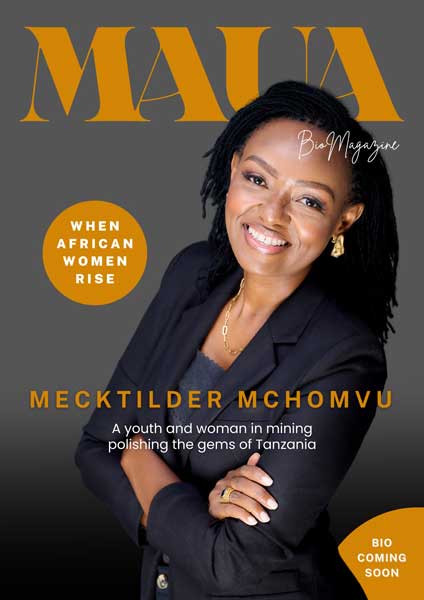

Precious Moloi-Motsepe, Stitching Medicine, Purpose and Possibility

Precious Moloi-Motsepe, Stitching Medicine, Purpose and Possibility

Image source: FASHION-SAFRICA-LIFESTYLE

There is a particular kind of silence that falls just before a runway show begins. Backstage, models wait, designers pace and the air is thick with anticipation. For Dr. Precious Moloi-Motsepe, that pause has always meant more than fashion. It is the moment where African creativity steps forward to claim space, dignity and economic value in a global industry that once dismissed it as peripheral.

Born in Soweto during apartheid South Africa, Moloi-Motsepe’s early life was shaped by constraint and contradiction. She grew up in a country that systematically limited Black aspiration, yet she was raised in a family that believed deeply in education as a form of liberation. That belief would take her first into medicine, a profession rooted in service, discipline and human care. She trained as a medical doctor, specialising in women’s health and for many years worked within clinical spaces where African women’s bodies, pain and resilience were daily realities rather than abstract concepts.

Medicine taught her precision. It also taught her how power operates, who is seen, who is heard and whose labour is undervalued. Over time, Moloi-Motsepe began to notice parallels between the health sector and the creative economy. African women were producing, sustaining and innovating, yet ownership and recognition rarely followed. Creativity existed yet infrastructure did not.

Her pivot into fashion was not a departure from purpose, but an expansion of it. In 2007, she founded African Fashion International (AFI), not as a vanity project but as an intervention. At the time, African designers struggled to access capital, global platforms and professionalised supply chains. African fashion was consumed globally, but rarely credited or commercially protected. AFI was designed to change that imbalance.

The early years were not glamorous. Building a continental fashion platform meant negotiating scepticism from both global gatekeepers and local institutions that failed to see fashion as serious economic work. Moloi-Motsepe insisted otherwise. She approached fashion with the same rigour she had brought to medicine: systems, standards and sustainability mattered. Designers were not just artists; they were entrepreneurs whose intellectual property deserved protection.

Under her leadership, AFI became a launchpad for African designers onto international stages, including New York Fashion Week. It also helped formalise fashion weeks in South Africa, contributing to job creation, skills transfer and export opportunities. Importantly, AFI centred African ownership. This was not about Africa being featured, it was about Africa leading.

Visibility, however, came with its own complexity. As a woman operating at the intersection of wealth, marriage and influence, Moloi-Motsepe was often flattened into labels that obscured her agency. She has spoken candidly about how women’s achievements are frequently attributed to proximity rather than capability. Her response has been consistency. Over time, the work speaks.

Beyond fashion, Moloi-Motsepe has played a significant role in philanthropy and social investment through the Motsepe Foundation, focusing on education, health, gender equity and youth development across Africa. Her approach to giving mirrors her approach to business: strategic, locally grounded and impact driven. She has repeatedly emphasised that charity without dignity is insufficient and that African development must be shaped by African priorities.

Her leadership philosophy is quietly radical. She does not position herself as a saviour, nor does she romanticise struggle. Instead, she speaks about building institutions that outlast individuals. She believes in creating platforms where others can rise without permission and in shifting narratives from consumption to creation.

Fashion, she argues, is not superficial; it is cultural memory made visible.

Moloi-Motsepe also understands the politics of aesthetics. Fashion, she argues, is not superficial; it is cultural memory made visible. When African designers control how Africa is dressed, styled and presented, they also influence how Africa is perceived. That control has economic and psychological consequences.

Today, she continues to work across business, philanthropy and creative leadership, often away from spectacle. Her influence is felt less in soundbites and more in structures, contracts signed, designers retained, industries stabilised. She has helped turn creativity into capital without stripping it of meaning.

“Sometimes, it is stitched together patiently, seam by seam, until an entire ecosystem begins to hold.”

There is no singular defining moment in Precious Moloi-Motsepe’s story. Instead, there is a steady accumulation of decisions rooted in care, strategy and long vision. She reminds us that leadership does not always announce itself loudly. Sometimes, it is stitched together patiently, seam by seam, until an entire ecosystem begins to hold.

In a world eager to consume African brilliance without investing in its survival, Moloi-Motsepe has chosen a different path. She builds, protects, and in doing so, she ensures that African women are not just seen, but sustained.

To date, Dr. Moloi-Motsepe is the co-chairs the Motsepe Foundation, championing education, gender equity and community development across the continent and serves as Chancellor of the University of Cape Town, proving that purpose and possibility can be stitched together to uplift communities and redefine African leadership.