Now Reading: Beyond the Last Mile Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo Our Unsung Shero

-

01

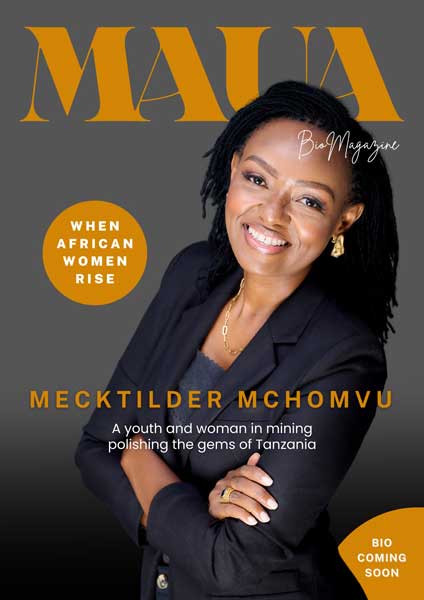

Beyond the Last Mile Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo Our Unsung Shero

Beyond the Last Mile Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo Our Unsung Shero

Cover image: Courtesy of Adrian Steirn: 21 ICONS

Beyond the Last Mile Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo Our Unsung Shero

By Hazel Friedman

“Nomathemba means hope; and hope is about the belief that life will be better.” Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo

Upcoming documentary, Beyond The Last Mile by Hazel Friedman and Zokufa Media

Healing Beyond the Last Mile

“I can’t go to sleep. I dare not shut my eyes when there’s still so much work to be done.”

Born-to-heal – Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo

These were not the first words I ever heard from Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo. But as our journey unfolded, they became part of the refrain that defines her essence: dedication, expertise, empathy and above all, an unyielding belief in healing through hope. These qualities earned her the Lifetime Achievement Award at the South African Health Excellence Awards on 8 November 2025 at the Sandton Convention Centre. Yet the honour, like her many previous accolades, remains only a footnote to a life devoted to healing the nation she loves.

A Life Shaped by Hope

At 87, Dr Cingo has reached heights that could justify rest. Instead, she continues to walk the foothills of service, returning to the chronically neglected Eastern Cape communities where she was born, and where so many still wait for care.

It is this lifelong pilgrimage that inspired the documentary Beyond the Last Mile, which I directed in partnership with Pam Zokufa of Zokufa Media Productions. Funded by the National Film and Video Foundation as part of its “Unsung Heroes” series, the film attempts to capture an urgent truth: hope is an active choice and Dr Lillian chooses it every day.

Still Walking the Foothills of Service

Hope fuels her mission to help heal a nation whose wounds, historic, present, physical and emotional, still run deep. It is this spirit, coupled with her charisma, humour, generosity and humility, that compelled us to tell her story.

The film traces her path from the rural hills of the Eastern Cape, through the trauma of exile, to her eventual return home to fulfil a calling rooted in childhood. Yet even a 40-minute documentary feels too brief to contain a life this vast.

The Wounds She Walks Toward

I met Dr Lillian in 2023 while documenting her work with One To One Africa, where she serves as a board member and key fundraiser. The organisation provides primary healthcare to at least 36 rural Eastern Cape villages, so-called “last mile communities,” because beyond their borders lies only wilderness.

On our way from Mthatha to Tshani near Coffee Bay, the tar road dissolved into a boulder-strewn, dust-drenched, and at times mud-soaked, track. A 70-kilometre journey took over three hours. While we jolted through this intractable landscape, swerving around craters that make Gauteng’s potholes resemble polished runways, Dr Cingo simply smiled.

“As a young girl growing up in Ndakeni near Flagstaff,” she recalled, “my parents made sure I went to school properly dressed. But once I was out of sight, I took off my shoes and walked barefoot, because I wanted to walk alongside those who had less. I still feel that way.”

On the Last Mile

Dr-Lillian-with-the-One-to-One-Africa-Mentor-Mothers

Today, despite democratic gains, these villages remain starved of basic services. Stunning natural beauty sits alongside deep poverty and systemic neglect. Women sustain the rural economy; HIV/AIDS remains widespread; unemployment hovers around 90%. Many households, mostly single-parent, survive entirely on SASSA grants.

Yet One To One Africa is reshaping this landscape. Through its ENABLE model, the organisation trains Mentor Mothers, local women who know the terrain, the families and their struggles, to bring healthcare directly to homesteads unreachable by ambulances. Mentor Brothers work with young men to address gender-based violence, disempowerment and addiction. With traditional leaders, the organisation establishes ECD centres and works with the provincial health department to help train professional healthcare workers in its community-based model.

It is the kind of grassroots, relational care that aligns perfectly with Dr Cingo’s ethos: healthcare not as charity, but as companionship and holistic healing.

Of Service and Quiet Rebellion

Dr Lillian’s lineage is rooted in service. Her great-great-grandfather, King Faku ka-Ngqungqushe, the last ruling monarch of the AmaMpondo kingdom (1818–1867), welcomed missionaries to help quell the violence devastating his people. Her ancestors championed education, faith, healthcare and women’s empowerment.

“We were born of noble blood,” she says, “but raised to value service. It wasn’t something we thought about. It was simply what we did.”

She was a gifted child: brilliant, book-hungry and instinctively empathetic. For a time, her family shielded her from apartheid’s cruelties. That protection shattered when her younger brother was jailed for reading a banned book by Bishop Trevor Huddleston. Another brother, an artist, not an activist, later died under suspicious circumstances. “My mother was never the same,” she says quietly. “Something in her broke.”

These losses forged her resolve not to avoid pain, but to transform it. “I’ve always had a sense of how people feel,” she told me. “Throughout my life, it’s always been about hope.”

Forged in Loss, Guided by Resolve

Already an acclaimed nurse, she longed to specialise in neurological science, a discipline apartheid barred Black women from pursuing. Encouraged by Dr Robert Lipshitz at Baragwanath Hospital, she applied to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and was accepted. Leaving her close-knit family was devastating, but she planned to return with the skills South Africa denied her. Destiny intervened.

In London, she met and married Reginald Hlongwane, accountant, weightlifter, human rights activist and co-founder (with Dennis Brutus) of SANROC, the non-racial sports movement that helped isolate apartheid South Africa. Their relationship was rooted in politics, jazz and literature.

A Healer in Exile

Their son, Jameson, was born in 1968. But he never visited South Africa as a child. When Dr Lillian tried to renew her passport, she was told she was no longer a citizen.

Their son, Jameson, was born in 1968. But he never visited South Africa as a child. When Dr Lillian tried to renew her passport, she was told she was no longer a citizen.

“Can you imagine the despair? The rage?” she asked. “My great-great-grandfather was King Faku. My parents served their country with dignity. And here I was, barred from home. For a moment, I understood what it felt like to throw a bomb. That’s how angry I was.”

Five years later, she obtained British citizenship. Her career soared. She received a special commendation from Queen Elizabeth II as one of Britain’s most outstanding neurological nurses. She went on to specialise in psychology, tropical diseases and HIV management. Yet while her professional life flourished, her marriage unravelled.

“They were both passionate and opinionated,” Jameson reflects. “Sometimes what brings people together later pulls them apart.”

“For Reg, everything turned to anger,” Dr Lillian says. “For me, it was still about hope.” Even after divorce and remarriage, Reginald continued to call her his wife. Before his death in 2022, suffering from dementia and loneliness, he begged her and Jameson to return his body to South Africa. They honoured his wish.

Rural Healthcare on Track

![]() By then, Dr Lillian had long returned to South Africa. From 1996 to 2008, she became the face and heart of Transnet’s Phelophepa Train, the “Train of Hope,” delivering healthcare to rural communities by rail.

By then, Dr Lillian had long returned to South Africa. From 1996 to 2008, she became the face and heart of Transnet’s Phelophepa Train, the “Train of Hope,” delivering healthcare to rural communities by rail.

![]() “She was the angel we were looking for,” says founder Lynette Coetzee, who became both colleague and lifelong friend. Known affectionately as “the twins” for their matching initials, they forged an unbreakable bond. Under their leadership, the Phelophepa train was honoured by the Order of St John and the United Nations. Both women received honorary doctorates from Dr Brigalia Bam during her tenure as Chancellor of the former University of Port Elizabeth. Other honours followed, including Dr Cingo’s recognition as one of South Africa’s 21 Icons.

“She was the angel we were looking for,” says founder Lynette Coetzee, who became both colleague and lifelong friend. Known affectionately as “the twins” for their matching initials, they forged an unbreakable bond. Under their leadership, the Phelophepa train was honoured by the Order of St John and the United Nations. Both women received honorary doctorates from Dr Brigalia Bam during her tenure as Chancellor of the former University of Port Elizabeth. Other honours followed, including Dr Cingo’s recognition as one of South Africa’s 21 Icons.

Today the train has expanded from one locomotive to several, though vandalised tracks hinder its mission, a reality that pains her deeply.

It was during her Phelophepa years that she met David and Jenny Altschuler, founders of the UK-based One to One Children’s Trust, pioneers in HIV/AIDS care during the era of AIDS denialism. Their treatment model, rooted in personalised care, now echoes throughout One To One Africa.

“These are the values Dr Lillian brings to us,” says Executive Director Gqibelo Dandala. “Expertise, empathy and the ability to walk with communities, one step at a time.”

Beyond the Last Mile

Her Phelophepa experience also shaped One To One Africa’s mobile clinic model, extending primary care to the most isolated homesteads. Her story reminds us that true care knows no boundaries, not even the last mile.

Travelling with her through the Eastern Cape’s rugged hinterlands and into the quiet suburbs of Sandton, where Jameson now lives with his family, revealed her many layers: a perfectionist with a rebellious streak, gently bending the rules when systems fail those they were meant to serve.

“She could have marketed herself as a brand and made millions,” Jameson says. “But she chose a humble path. Her happiness lies in helping others.”

At her core is unadorned simplicity. Her pioneering work, her faith and her distinctly personal feminism are all rooted in family and ubuntu, I am because we are.

A Healer for Our Time

In-2025-Dr-Lillian-received-the-South-African-Lifetime-Achievement-Award-for-Health-Excellence.

In an era obsessed with youth, age is often dismissed as irrelevance. But Dr Lillian is still seen, still heard, still vital. Though she embraces aspects of British culture, she remains a daughter of South African soil. Even when the promised land resembles a land of broken promises, she continues to serve, across borders, across generations.

It is this unbroken thread of service that makes Dr Lillian Nomathemba Cingo one of South Africa’s most essential healers. And because of her, hope, long deferred, is making a comeback.