Now Reading: Funke Opeke, Building the Invisible Infrastructure Africa Runs On

-

01

Funke Opeke, Building the Invisible Infrastructure Africa Runs On

Funke Opeke, Building the Invisible Infrastructure Africa Runs On

Image source : Harvard Business School

On the Atlantic coastline of West Africa, where the ocean meets land with relentless force, a fibre-optic cable disappears beneath the waves. It is not dramatic to look at and no ribbon-cutting ceremony can capture what it carries. Yet for millions of Africans, that cable has quietly altered the possibilities of work, education, commerce and connection. Funke Opeke understands this kind of power, the kind that does not announce itself, but changes everything.

Opeke was born 1961 in Nigeria and raised between Lagos and the United States, moving through worlds that exposed both abundance and absence. She trained as an electrical engineer, building a career in American telecommunications firms where infrastructure was assumed, reliable and largely invisible. In those environments, technology was not aspirational; it was foundational. The contrast with Nigeria was impossible to ignore.

Returning home in the early 2000s, she encountered a digital landscape shaped by scarcity. Internet access was slow, expensive and fragile. Businesses struggled to operate at scale. Innovation was throttled by bottlenecks few global technology leaders ever had to think about. While many saw these limitations as structural inevitabilities, Opeke saw an engineering problem and therefore, a solvable one.

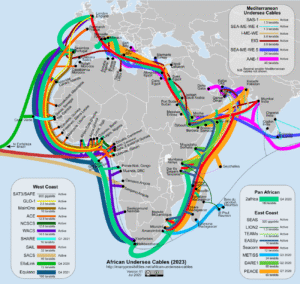

Her insight was simple and audacious: Africa did not lack talent or ambition; it lacked infrastructure. Specifically, it lacked high-capacity, reliable broadband connectivity. In 2008, she founded MainOne, a company that would go on to build a 7,000-kilometre submarine cable system connecting Nigeria to Europe, with extensions along the West African coast. At the time, this was not just a technical undertaking; it was a political, financial and psychological risk.

Securing investment for such a project required convincing institutions that Africa was worth long-term bets. As a woman in a heavily male-dominated engineering and finance ecosystem, Opeke faced layered scepticism. Questions were asked, about feasibility, demand, leadership, that rarely follow similar projects elsewhere. She has spoken openly about boardrooms where she was the only woman, the only African, or both. Her response was preparation. She arrived with data, models and a command of the technical details.

When MainOne’s cable went live in 2010, it marked a turning point. Internet costs dropped. Speeds increased. New businesses emerged. Nigeria’s technology ecosystem, now globally recognised, found the bandwidth it needed to grow. What followed was not an overnight transformation, but a compounding one. Infrastructure, once laid, invites imagination.

Opeke did not stop at cables. She understood that connectivity without local capacity would reproduce dependency. MainOne expanded into data centres and cloud services, ensuring that African data could be hosted, secured and managed on the continent. This was about digital sovereignty long before the term became fashionable. Who controls the servers controls the future.

Her leadership style is precise, disciplined and deeply technical. She does not trade in hype. She speaks in systems and timelines, in reliability and redundancy. There is little interest in personal branding; visibility, for her, is a by-product of execution. Yet her presence matters. For African women engineers and technologists, she represents a rare and powerful mirror, someone who built scale without asking for permission.

In 2022, MainOne was acquired by Equinix, a global data infrastructure company, in a landmark deal that validated years of patient building. The acquisition did not mark an exit from purpose, but a transition into broader influence. Opeke continued to advocate for Africa’s digital readiness, infrastructure investment and policy environments that enable, not stifle, innovation.

She is careful about narrative. Opeke resists portrayals that frame African success as exceptional rather than expected. She speaks about ecosystems, not heroes; about teams, not lone visionaries. In interviews, she often redirects attention to engineers, planners and operators, the people who keep systems running when no one is watching.

There is also a quiet gender politics to her work. Telecommunications infrastructure is rarely imagined as a women’s space. Opeke occupies it without apology, refusing both invisibility and tokenism. She has said that competence is not enough; women must also be willing to claim authority. Her own career is evidence of that truth.

At a time when Africa is often discussed as a consumer of technology, Opeke’s work insists on a different framing. Infrastructure is agency. Ownership is power. The future cannot be downloaded; it must be built, cable by cable, and server by server.

Image Source – Equinix Blogs

Funke Opeke’s legacy is not a single company or deal. It is the normalisation of possibility. The fact that a generation of African entrepreneurs can assume fast internet, cloud access and global reach is not accidental. It rests on decisions made years earlier by a woman who understood that the most transformative work is often the least visible.

You do not see the cable when you log on. But it is there, steady, deliberate and enduring. Much like the woman who put it in place.